Feb 2012 The new Judges and Ranking Handbook is available in the Download area. Thanks to Pat Rice, Carl Meeks and Ray Tom for their hard work.

Happy Chinese New Year and DVD Sale

Jan 2012 May the Chinese New Year bring you happiness, good luck, and wealth.

Don’t miss our Chinese New Year BOGO DVD sale. When you buy one DVD, get a second one of equal or lesser value FREE. This sale ends on Tuesday, January 24. After ordering the first DVD, please email fanghong@yangfamilytaichi.com to say which free DVD you want.

Lengthening And Peng

The Third Rep: 2004-08-31

by Jerry Karin

We publish here a translation of the second section of the first chapter of Chen Style Tai Chi Chuan, a seminal 1963 work by Shen Jiazhen and Gu Liuxin (this part was written by Shen Jiazhen).

I used the text contained in Renmin tiyu chubanshe, Taijiquan Quan Shu, 1988, which is a reprint of the original, 1963 edition plates.

Jerry,

2004-08-31

The Second Characteristic: An Exercise of Springy Lengthening of the Body and Limbs

Boxing manuals dictate:

Gently lead the head to press upward (xu ling ding jing), sink the qi to the dantian.

Reserve the chest and pull up the back, sink the shoulders and droop the elbows.

Relax the waist and round the crotch, open the kua and bend the knees.

Spirit collected and qi kept, body and arm lengthened.

From the 4 sayings listed above we can see that “Gently lead the head to press upward (xu ling ding jing), sink the qi to the dantian” are lengthening of the body, “Reserve the chest and pull up the back” is to lengthen the back by using the front of the chest as a support; “sink the shoulders and droop the elbows” is to lengthen the arm and hand; “Relax the waist and round the crotch” as well as “open the kua and bend the knees” cause the legs to freely rotate, which is the result of lengthening the legs under the conditions of this type of special posture. Therefore the footwork of taiji requires, under the conditions of rounded crotch, relaxed waist, open kua and bent knees, the use of rotating ankle and leg in order to alternate full and empty. Externally this is manifest as the silk reeling energy of the legs, but actually internally this tends toward the lengthening of the the legs.

This series of lengthening motions additionally generates a lengthening of the entire body, causing torso and limbs to create a springy flexibility and produce peng energy, and because the entire body is lengthened, this naturally stimulates the spirit to lift. Because of this, you need only have this lengthened posture to avoid generating the defect of strident force (brute force), making favorable conditions for naturally relaxing open and lengthening torso and arms. Therefore “An exercise of springy lengthening of the body and limbs” is the second characteristic of taijiquan.

I. Lengthening the torso and limbs

As mentioned above, when practicing taijiquan you must lengthen the torso and limbs in order to increase the flexibility of the entire body; only with this flexibility can one go on to create peng energy. That is to say, peng energy arises from springy flexibility and flexibility arises from lengthening of torso and limbs. As to how each part of the body is to lengthen, we will now explain according to the boxing manuals:

- Gently lead the head to press upward (xu ling ding jing) and sink the qi to the dantian — What is referred to as pushing up energy and gently lead is to take a forward pressing energy (ding jing) and lead it gently upward; sinking the qi to the dantian is to take the qi and make it sink down toward the dantian; combining these two there is an intent to pull apart in opposite directions, which causes the torso to have a feeling of lengthening.

- Reserve the chest and pull up the back — “Reserve the chest requires that the chest neither puff out nor cave inward, allowing the chest to function as a support to elongate the backbone, because in physics a weight-bearing column is not allowed to be bent. Relying on this support to pull up the backbone is to elongate the backbone. In this regard, beginners are cautioned not to regard curving or hunching the back as pulling up the back, because if you hunch the back then the chest will cave inward and in this way lose the function of the front of the chest supporting the back, thereby not only causing the back to lose springy flexibility but also harming ones health.

- Sink the shoulders and droop the elbows — The main use of sinking the shoulders is to make the arms and shoulders, because they droop downward, become solidly connected. Only if the arms and shoulders are solidly connected can the arms have root. At the same time, owing to the lowering of the elbows, the area from the elbows to shoulders is lengthened. When the arms and hands proceed in spiraling, silk-reeling motions they use the elbow as a center. At the same time, the lowering of elbows and standing of wrists can cause the area between elbows and wrists to lengthen. Therefore the sinking of shoulder, drooping of elbow and standing of wrist is the lengthening of the entire arm.

- Rotation with opened kua and bent knees — This is the lengthening of the legs. The legs are standing on the surface of the ground, so lengthening them is relatively difficult. And so setting forth the requirement to open kua and bend knees, we require that within this defined posture (rounding crotch) we use spiraling movement to alternate full and empty, and this mainly manifests itself in the rotations of the knee. In this way, as the outside rotates outward this causes the outside to lengthen and the inside to contract. Matching up this rotation of the leg to the rotations of the arms, hands and body creates whole-body rotation and with gradual improvement one can attain to total body strength such that “the root is in the heels, emitting through the legs, controlled in the waist and manifested in the hands”.

Summing up the above-mentioned four rules, we can see that taijiquan requires lengthening of torso, arms and legs. Hence not only does this springy flexibility through lengthening create the basic peng energy of taijiquan, but it can also naturally lift people’s spirit and avoid the defect of inappropriately rousing strength to create brute force. 1

II. The Physical Function of Lengthening Body and Limbs

When energy is applied to muscle it can undergo a finite elongation, but once the external cause of the lengthening is removed it immediately returns to its original shape. This is the inherent flexibility of muscle tissue. Most common exercises train and improve this kind of flexibility. In accord with human physiology, this type of muscle flexibility in expansion and contraction can give rise to the following four functions:

- It can improve the ability of the muscle itself to expand and contract and facilitate circulation in the dense net of capillary vessels within the muscle.

- It can increase flow of fuel and waste products within the cells and stimulate the entire metabolism.

- It can promote the exchange of gases within the muscles and all other organ systems.

- It can increase the amount of oxygen within the body and at the same time raise the rate of oxygen efficiency within each of the organ systems.

Taijiquan is not a simple movement of the limbs. Externally it manifests as the spirit in motion with highly complex postures while hidden within it is the spirit gathered and qi collected, such that the the mind moves the qi. This has been elaborated above in the description of the first characteristic. Additionally, taijiquan not only trains both inner and outer, but also, under the conditions of entire body and limbs elongated, is a process of winding and unwinding, forward and reverse silk reeling. In this way it not only brings about excellent training in flexibility for the muscles, but also raises the rate of blood circulation, thus curing diseases caused by poor circulation. This is an important result of the elongation of body and limbs and the lifting of the spirit in taijiquan. Also, the springy and flexible movements of taijiquan have an observable effect in lowering blood pressure, because as the muscles expand and contract they are able to create adenosine triphosphate (? sanlinsuan and xiantaisuan), substances which are able to dilate the blood vessels. At the same time, as we perform these movements in which each part is connected together, inside the muscles the number of opened capillary vessels increases by several times, thus broadening the cross section of blood vessels carrying the blood and so lowering the blood pressure. Additionally, when you practice taiji, because the muscles are repeatedly expanding and contracting, it is difficult for the blood vessels to harden. The process of winding and unwinding in forward and reverse silk reeling particularly prevents the hardening of blood vessels. People who have practiced taijiquan for many years can, as they practice, feel the blood vessels expanding open in their back and limbs. As soon as they begin to do the exercise they feel loose and comfortable, and if they are unable to practice for a while, there is a sensation of being closed up. These phenomena are the result of the increase and decrease of the number of opened capillaries.

III. The Eight types of Jing and the Springy/Flexible Peng Jing

Taijiquan requires that we use intent rather than brute force, but this is not to say that we use intent but not strength (jing), because taijiquan is constructed of the eight types of jing. All of these eight types of jing contain elongated springy flexibility, that is why they are called jing (energy) rather than li (force). Although these eight jing have different names, in reality there is only a single peng jing, the other seven merely different terms for the same thing in different positions and functions. Therefore taijiquan can also be called by the name peng jing quan. We will now analyze the content of these eight jing in order to further aid in grasping the second characteristic:

- Within the context of the entire move, when the palms rotate from facing inward to facing outward, that is called peng jing.

- Within the context of the entire move, when the palms rotate from facing outward to facing inward, that is called lü jing.

- When both arms simultaneously use peng jing and intersect to peng outward, that is called ji jing.

- When the palms press downward encircling somewhat and while not losing contact, exercise peng downward, that is called an jing.

- The paired separating peng jing when the two arms cross going left and right or forward and backward is called cai jing.

- When peng jing is curled up and then within a short distance fiercely strikes out, that is called lie jing.

[under construction]

Footnotes

[author’s footnotes from original Chinese]

[1] Lengthening causes the body and arms to have an internal sensation of thin and long whereas inappropriately rousing strength causes the body and arms to have a sensation of thick and short. Therefore lengthening body and limbs naturally does not cause the defect of rousing strength and creating brute force.

Translation Copyright © 2004 Gerald N. Karin. All rights reserved.

Empty and Full

The Third Rep: 2004-01-02

by Jerry Karin

We have been having an interesting discussion on the discussion forum regarding the meaning of the fourth of Yang Chengfu’s Ten Essentials: distinguish full and empty. To shed more light on this subject, we publish here a translation of the first half of the Empty and Full section of the first chapter of Chen Style Tai Chi Chuan, a seminal 1963 work by Shen Jiazhen and Gu Liuxin (this part was written by Shen Jiazhen). Second half coming soon. This translation is still a work in progress. I would enjoy hearing your comments and corrections.

I used the text contained in Renmin tiyu chubanshe, Taijiquan Quan Shu, 1988, which is a reprint of the original, 1963 edition plates. I was able to get a slightly better scan of the pictures from a Taiwan edition put out in 2002 by Da Zhan Chubanshe, reset in traditional characters, so I have reproduced the figures from that edition (this reset edition unfortunately has introduced some typographical errors into the text).

The majority of this material is identical to what the Yang family teaches, though I cannot recall ever hearing or reading any discussion from them regarding empty and full in the arms. The bow posture shown in figure 8 differs slightly from Yang Chengfu in that his torso leans forward slightly more than shown here, in my opinion.

Jerry,

2004-01-02

The Fourth Characteristic: An Exercise of Empty and Full in which the Body Stands Centered and Upper and Lower Body are Coordinated

Boxing manuals dictate:

- “Intent and Qi must change nimbly, only then can there be free change of direction; that is what is meant by ‘you must apply intent when changing full and empty’.”

- “Full and empty should be clearly distinguished, each place has its full and empty, all places always have this part-empty part-full quality.”

- “The body must stand centered and stable to handle all eight directions”; If upper and lower coordinate others will have difficulty invading.”

- “Coccyx centered and spirit infused in the apex”; “From top to bottom a single line.”

As the above four rules explain, in all movement in taijiquan one must distinguish full and empty. If in movements you can distinguish full and empty while changing and transitioning, you can have long-lasting endurance without getting tired, making this the most economical form of kinetic activity. For this reason, when you practice taijiquan the two arms must have empty and full, the two legs must have empty and full. Especially important, the left leg together with left arm, right leg together with right arm, must have empty and full which coordinates upper and lower, that is to say if the left arm is empty the left leg should be full, if the right arm is full the right leg should be empty. This tunes internal energy and causes it to maintain a centered, central linkage. In addition when from the starting point of ‘within the empty there is fullness and within the full there is emptiness’ we add that in every place there is always this part-empty part-full quality, it causes internal energy to acquire a centered quality which is not biased toward one way or another. Beginners can use large-scale emptiness and fullness in their movements, gradually training towards small-scale emptyness and fullness, and finally arriving at the realm wherein internally there is empty and full but externally there doesn’t appear to be any emptiness or fullness, which is the greatest level of skill for regulating full and empty.

The key to nimbly changing full and empty depends on nimbly changing intent and qi, while at the same time ‘staying in the center and not departing from the proper position’1 and keeping the internal energy centered. For this reason when you practice you must regulate full and empty with ‘coccyx centered’, ‘stable to handle all eight directions’, ‘gently leading the energy of the apex upward’ (trans note: xu ling ding jing, which I have translated somewhat differently here according to Shen Jiazhens gloss of the term on page 12 of his book), ‘from top to bottom a single line’. Therefore ‘regulating full and empty with body standing centered, upper and lower coordinated’ becomes the fourth characteristic of taijiquan.

I. The relative proportions of full and empty

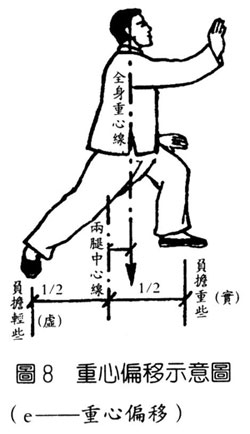

Figure 8. Center of Gravity Offset

According to the principles of taijiquan, within all movements we must clearly distinguish full and empty, and so when we practice we must attend to making our movements such that in all places we have this part-empty part-full quality. In order to achieve this regulation of full and empty we must first recognize the true meaning of full and empty. ‘Empty’ does not mean totally devoid of strength; ‘full’ in turn does not mean totally occupied. In the case of the legs, for example, empty does not mean this leg bears no weight at all, nor does full mean this leg bears all the weight (positions where one is lifting the foot, standing on one leg, or getting out of entrapment [chinna] excepted), but rather empty is merely bearing slightly less weight than full. The origin of this full/empty terminology, from the point of view of mechanics, is owing to the fact that the center of gravity of a human body generally is more toward one side or the other. When the center of gravity is tending slightly more toward the right side, this makes the right leg full and the left empty; when it tends slightly more to the left side, then the left leg is full and the right empty (as in figure 8) As we have said above the movement energy of taijiquan is generated from the switching of the center of gravity from one side to the other. If there is no differential between the two, in other words if the center of gravity is placed precisely in the midline of the body, that would create ‘doubling’ (shuang chong) 2, losing movement energy and creating the defect of stagnant doubling. If however at this point if you lightly ward off with both arms, it can become the effective arms of ‘double sinking’ 3 ,causing the movement to once again achieve the movement energy to change.

Figure 8 Explanation:

The dotted line (near center line of body) shows the center of gravity of the entire body

The dotted line to the left of that and just under the back leg shows the center between the two feet.

Vertical text on left: ‘bears slightly less weight’

Vertical text on right: ‘bears slightly more weight’

Character in parens on lower left: ’empty’

Character in parens on right: ‘full’

Full and empty are not fixed, they change following the transformations of the moves of the form. Beginners should use relatively gross full and gross empty postures, such as 20/80 (20/80 represents the ratio of weight distribution, so if the entire body weighs 100 pounds, one foot would bear 20 pounds and the other 80). As you become more accomplished, you should change to relatively lesser full and lesser empty postures, such as 40/60 etc. After having gone through this process of training toward the more compact, owing to the slighter degree of movement, you can cause the alternation of full and empty to be even more nimble. The inner source of changing freely lies in freely changing intent and qi, and owing to that one can attain to not being stuck in one direction or one spot: for example when in some move one ought to place ones attention on the left hand, then one is able to effortlessly and immediately switch to the left hand. 4 This can cause one to have a kind of ambidextrous feeling in practicing taiji, generating a sensation of freely rotating like a ball rolling on a plate. From the point of view of taiji postures, this means that in no transition is one caused to have ones ‘center departing from its proper position’; only by not departing from the proper position can one switch toward left, right, backward or forward without restriction. If the body is inclined toward one side as you change direction, you must undergo some adjustment before you can make the change. This amounts to a gap in your movement, and moreover because you have added in an additional operation, it slows down your movement, possibly missing some opportunity. In taiji technical terms, this is known as shiji ‘missing an opportunity’. Missing an opportunity and losing position are major defects in taiji, so in switching full and empty, it is only under conditions where the body stands centered that one can attain to the requirement for changing nimbly. This is an important key which one must grasp thoroughly.

II. Three basic types of full and empty

(1) Full and empty in the legs

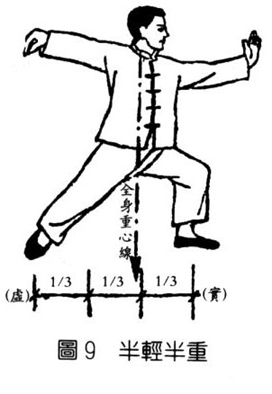

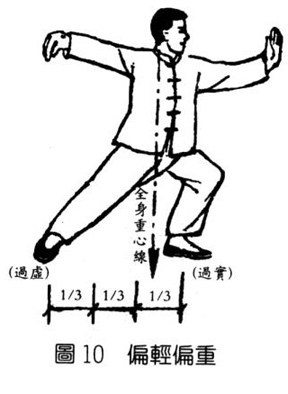

The division of full and empty in the legs is simply that one leg supports more weight, and one leg supports less. According to the principles of mechanics, if the center of gravity of the body is placed in the inmost one-third of the area between the two legs, this causes both of the legs to have a purchase, and this is called ‘half-light half-heavy’. 5 (as in figure 9) If the center of gravity goes beyond the range of the inmost one-third, then the empty foot, because it is too empty, will undergo a phenomenon of floating up, causing a defect called excessively light and excessively heavy (pian qing pian zhong). 6 (as in figure 10)

In addition, when you are moving or emitting energy (fajing), the movement must be such that you retain some slight reserve. Even after you have released energy, the four limbs still should not be 100% extended straight. Because once you have straightened them, when you then go to switch full and empty, you would have to first change the straight to bent and only then reverse the extended and retracted. But if your arms and legs retain some slight reserve, then you can just rotate naturally, without wasting time reversing and this gives you the basis to make the moves capable of being automatic.

In summary, the requirement for taijiquan in regard to the legs is, at all times and places, to be able to reverse this part-full part-empty state, and in particular you must gradually make the differentiation smaller, so that the switch can become quicker. If you cannot change empty and full in the legs quickly, you won’t be able to respond to the changes in the arms, causing it to be impossible to coordinate upper and lower, so that you’ve become divided into two separate parts, destroying the required unity of the entire body in movement.

Figure 9. Half Light Half Heavy |

Figure 10. Excessively Light Excessively Heavy |

|

Explanation: The dotted line (near center line of body) shows the center of gravity of the entire body Character in parens on lower left: ’empty’ Character in parens on lower right: ‘full’ Figure 10. Excessively Light Excessively Heavy |

Explanation: The dotted line (near center line of body) shows the center of gravity of the entire body Characters in parens on lower left: ‘too empty’ Characters in parens on right: ‘ too full’ |

(2) Full and empty in the arms

Whenever energy circulates to an arm to ward off, this arm is empty. When it circulates such that the arm sinks downward then this arm is full. The movements of the two arms in taijiquan, like those of the legs, must also be divided into full and empty, so for example when both arms push simultaneously, as in the ‘six sealings and four closings’ (liu feng si bi) move, you should also divide them up by 40/60. But the proportions used for full and empty in the arms are slightly different from the legs: after you have achieved some skill (gongfu), except for a few individual moves, the proportion is still in the 30/70 to 40/60 range; the division is still relatively gross. This is because in order to achieve a sunken, extended calmness, you concentrate on one side, such that the rule is to make one side primary and the other side secondary. It is particularly important for not only the limbs to switch nimbly, but the intent and qi to switch nimbly, so that the intent and qi are not stuck on one side, especially the right arm.

(3) Full and empty in arm and leg

The division of full and empty which requires the most work is the type of division of full and empty occurring between an arm and a leg. Also from a health maintenance and martial point of view the most effective type is this division between arm and leg, upper and lower. This is the essence of how to cause stepping to be smooth and connected. The requirement and method is: if the right hand sinks down and is full, the right leg must be empty. Then when the right hand changes to warding off upward and becomes empty, the right leg follows the hand above and changes to full. Proceeding in this way is termed ‘distinguishing full and empty in coordinating upper and lower body’. In the taijiquan classic “Song of Pushing Hands” (da shou ge) it says: “You must be diligent about ward off, rollback, press, and push, if upper and lower coordinate others will have difficulty invading,” so you can imagine how important this is. Therefore when you practice taiji you must thoroughly inspect each move to see if it accords with this requirement to coordinate upper and lower. If we look at the performance of one round of taiji, there are so many different types of postures and so many different kinds of transitions between postures. In order to achieve this coordination of upper and lower you must naturally expend a good deal of effort to really grasp this and become proficient at it. In this type of switching, aside from the case of stepping, where hand follows foot in switching full and empty, the majority of instances are all those where foot follows hand in switching full and empty. Overall, if you can achieve this hand and foot, upper and lower type of full and empty then the position of the center of gravity will not leave the inmost one-third of the range between the two legs, causing both legs to maintain a purchase, so that internal energy can stay centered; only when internal energy is centered can one handle all eight directions. This type of full and empty, rendered via positioning of the feet on the floor, is to have full within empty and empty within full. By preparing this full and empty integrated with upper and lower coordination the footwork can become nimble and not stagnant, advancing and retreating become natural, and only then can you connect to and follow an opponent without letting go or opposing force with force. Likewise, when you have become proficient at push hands, you need only attend to the arm in contact with the opponent, and you won’t need to be distracted about the other arm and the legs, because of this habit you have gained of upper and lower coordinating. Having achieved this automatic coordination is the key to seeking quiescence in movement and actually obtaining it.

Getting a Grasp on Empty and Full

[under construction]

Light and Heavy, Floating and Sinking in Regard to Empty and Full

[under construction]

Footnotes

[author’s footnotes from original Chinese]

[1] ‘Staying in the center and not departing from the proper position’ (zhong tu bu li wei)refers to the body’s center of gravity not leaving the inmost one-third of the area between the two legs, see figure 9.

[2] Doubling is when the two legs are not separated into full and empty, making double full; when the two arms are not separated into full and empty, that is also regarded as doubled full. For this reason they become doubled, to the point where we have filled them solid and stuck fast, so that one cannot change nimbly, so this is a defect.

[3] Double sinking is when although the two legs are not yet distinguished into full and empty, or only very faintly distinguished, they become double full, but both arms are completely empty or only very faintly distinguished into full and empty. This way they have become ‘leaping empty’, as in the cross hands move, becoming coordinated upper and lower double full and double empty. This is called double sinking. At this time although the arms are both empty and the legs both full, internally there is still the distinction of base and point, so it is not a defect.

[4] “This refers to the fact that most people are accustomed to using the right hand, but when at times they ought to attend to the left hand they are still paying attention to the right hand.

[5] ‘Half’ is when the center of gravity of the body is placed in the inmost one-third of the area between the two legs so that both legs are pressing against the ground, but one more heavily than the other, therefore this is called half footing (ban you zhuoluo), or half light half heavy (ban qing ban zhong). This is the correct posture.

[6] ‘Excessive’ is when the center of gravity goes beyond the range of the inmost one-third, causing one foot to be especially heavy so that the other foot floats on the ground, forming too much weight on one side and so of course the other side is too light, in other words inclined so much that it has no purchase, sometimes called ‘excessively light and excessively heavy (pian qing pian zhong), which is a defect.

Translation Copyright © 2004 Gerald N. Karin. All rights reserved.

Snippets

The Third Rep: 2003-05-06

by Jerry Karin

I’ve been reading a great deal in Chinese and have had a lot of luck in finding things I wanted to read, chiefly due to the kind offices of Louis Swaim. I am going to present some snippets of my readings in English translation here. I will be adding these as I get them typed up, so check in from time to time for new additions.

Jerry,

2003-05-06

Researches in Taijiquan

2003-05-12, I cannot vouch for the authenticity of the following anecdote, which comes from Wang Jiaxiang’s Researches in Taijiquan, Yang Style Volume, p 30:

In the early years of the Republic (started 1911) Shen Jiazhen learned taijiquan from Yang Chengfu for a protracted period. He once asked Yang Chengfu: “As far as fa jing goes, what’s the best move to practice to improve strength and most easily increase ability (gongfu)?” Yang Chengfu taught him a move:

The right fist was lifted high, protecting the head. The eye of the fist and the tiger’s mouth faced backward. The left fist protected the right ribcage, with the eye of fist and tiger’s mouth facing the underarm and the elbow hanging down near the left ribcage. The left leg was lifted till the (thigh) was level, protecting the crotch. It suddenly dropped, striking the ground and making a sound. Then a step forward with the right foot, the forward knee bending, back leg extending, the pair of fists both rushing forward using reverse reeling energy. The left fist was held high protecting the head, the eye of the fist and tiger’s mouth facing backward. The right fist protected the left ribcage with the eye of fist and tiger’s mouth facing the underarm and the elbow hanging near the right ribcage. The right leg was lifted till the (thigh) was level, protecting the crotch. It suddenly dropped, striking the ground and making a sound. Then a step forward with the left foot, the forward knee bending, back leg extending, the pair of fists rushing forward using reverse reeling energy.

The energy was complete, crisp and quick, with hard and soft alternating. Shen was puzzled by it. The taijiquan that he had learned following Yang Chengfu did not include this movement, but he didn’t dare ask more about it. Only later when Shen learned the second routine cannon fist from Chen Fake did he realize that what Yang Chengfu had shown him earlier was the Zuo Chong and You Chong (left and right charge) moves from Chen style cannon fist. This proves that the Yangs, up until Yang Chengfu, were familiar with Chen Old style second routine.

Taiji Quan, Qi Ren Qi Gong

2003-05-06, The first snippet is a couple of short excerpts from a book called Taiji Quan, Qi Ren Qi Gong (“Tai Chi Chuan, Unusual Personages and their Unusual Abilities”) By Yan Hanxiu. (In my Taiwan reprint edition this is on page 132, talking about Yang Zhenduo).

In the past when earlier generations of the Yang family taught, this was generally always a matter of the teacher at the front of the class demonstrating and the students following along. Seldom did they lecture or discourse about the principles of the movements, or taiji theory. This is how Yang Zhenduo himself learned. Over several decades from his teaching experience and his own practice, he has put together a method of teaching which really works. He has boiled down the requirements for each move into a set of short narrative phrases which are great for practice and easy to remember. When Yang Zhenduo teaches he simultaneously recites the narrative and demonstrates the movements himself.

For example, for right ward off his boiled down narrative is:

zhong4xin1 lue4 xiang4 you4 Shifting the weight a bit towards the right, yao1dai4 zuo3 jiao3 kou4 with the waist turn the left foot in, yao1 yao4 xiang4 zuo3 zhuan3 waist must turn toward the left, zhong1xin1 xiang4 zuo3 yi2 center of gravity shifts leftward, you4 bei4 huan2 zai4 zuo3 bei4 xia4 fang1 right arm circles under left arm, liang3 bei4 xiang1 he2 the two arms closing together, ti2 tuei3 man4 bu4 pick up the foot and step out, gong1 tuei3 you4 bei4 peng2 qi3 bending the knee ward off with right arm zuo3 shou3 zhi2 yu2 you4 bei4 zhou3 wan3 zhi1 jian1 left hand positioned between right elbow and wrist.

Note: I’ve long thought that the kou jue or short narrative was one of the chief pedagogical innovations of Yang Zhenduo. Another is the more precise terminology he employs for angles and degrees (feet, turns, etc).

Here is another snippet from an article in the same book about Yang Hou Zhuqing, the widow of Yang Chengfu.

After Yang Chengfu passed away, there came into her keeping a book of ancestral instructions and a hand-copied copy of a book of recipes for curing martial arts injuries. The ancestral instructions recorded the narrative of Yang style founder Yang Luchan as well as each successive generation of family inheritors of the style. The hand-copied book of recipes for curing martial arts injuries recorded secret recipes showing when a particular body part was injured how to treat it etc. When Yang Chengfu was teaching, if his students were injured while practicing they would use wine steeped in the herbs from the recipe in the book, rubbing it in and getting immediate relief. She regarded these two objects as treasures, kept them locked in a box, and never allowed anyone to see them.

During the Cultural Revolution some ignorant people came to search the house. Emptying out boxes and shelves, when they pulled these two objects out from the bottom of the box and saw that the paper was old and yellowed, they reviled it as part of the ‘Four Old things” and destroyed them on the spot. She and Yang Zhenguo stood on one side watching, hearts bursting with sadness but with no recourse. The Yang family martial arts have been passed down by other means, but the book of ancestral instructions and book of recipes perished in this way.

Translation Copyright © 2003 Gerald N. Karin. All rights reserved.

Silk Reeling

The Third Rep: 2002-08-26

by Jerry Karin

Much of the literature available in English about the topic of silk reeling is of the puff piece sort, leaving one with the impression that silk reeling is important but failing to provide much in the way of concrete, down-to-earth information. I came across an excellent and important article in Chen Style Tai Chi Chuan, a 1963 book by Shen Jiazhen and Gu Liuxin. What follows is a translation of the silk reeling section of the first chapter of that book (this part was written by Shen Jiazhen). I think that practitioners of all styles will find this quite interesting. This translation is something of a work in progress. I would enjoy hearing your comments and corrections.

Silk reeling is a subject rarely talked about in Yang family taiji. Though you don’t hear much discussion of the topic under this name, actually Yang style also does contain most of the same elements elaborated as silk reeling in other styles (though the shape of the hands in Yang Chengfu style – fingers slightly curved, palms slightly extended – is different from that shown in figure 1 below).

Jerry,

2002-08-26

The Third Characteristic: Movement with Spiraling, Forward and Backward Silk Reeling

Boxing manuals dictate:

Moving energy (yun4 jing4) is like pulling silk

Moving energy is like unwinding silk (silk reeling)

As you open and extend as well as draw in, you must never depart from the taiji [symbol shape]

Once the most subtle hand begins to traverse a taiji [circle], the traces of it are completely transformed into nothingness.

From the 4 rules listed above we can see, Tai Chi Chuan movements must be in a shape like pulling silk. Pulling silk [from a cocoon] is done by a circular motion, and because it combines pulling straight and circling, naturally it forms a spiraling shape, which is the unification of the opposites of straight and curved. Silk reeling energy or pulling silk energy both refer to this idea. Because in the process of unreeling, extending out and pulling back the four limbs likewise produce a sort of spiraling shape, therefore the boxing manuals say that whether in large, extended movements or compact, small movements, one must absolutely never depart from this type of Tai Chi energy which unites opposites. Once one has trained in this thoroughly, this silk reeling circle tends to become smaller the more one practices, until one gets to the realm where there is a circle but no circle is apparent, at which point it is known only by intent. 1 This is why the third characteristic of Tai Chi Chuan is that it is an exercise which unifies opposites with silk reeling, both forward and backward.

I. The Essence of Movement Like Silk Reeling

When we say in Tai Chi Chuan the movements must be like unreeling silk, or like pulling silk, these two images both mean that the shape of the movements is like a spiral. At the same time that this spiraling must go in a curve – much like the way a bullet follows the spiral rifling in a gun barrel so that as it moves through space it has an inherent turning in a spiral shape – it also has a trajectory along another line like that of the bullet hitting a target. Silk reeling energy in Tai Chi Chuan has this same kind of quality.

As we have already explained, movements must be like silk reeling, but how in our actual movements are we to realize this theory? In fact it’s quite ordinary and simple: within the requirements for the entire movement, as you move, the palms rotate from facing inward to outward or from facing outward to inward, 2 causing them to form a shape like the Tai Chi symbol (see figure 1). At the same time, owing to the rotation of the palms inward and outward, there is manifest in the upper body a turning of the wrists and upper arms and in the lower body a turning of the ankles and legs 3, and in the torso this is manifested as turning of the waist and backbone. Combining the three, this forms a curving line turning in space with its “root in the feet, commanded by the waist, and manifested in the fingers”. This is a requirement which we must achieve in Tai Chi Chuan. Because of this the boxing manuals particularly point out that whether in broadly extending out or in shrinking and drawing in, we can never for a moment depart from the Tai Chi energy of rotating the palms and turning the wrists and upper arms. This is precisely like the way the earth turns on its own axis at the same time it moves in a curve around the sun. That is why Tai Chi energy is not circling in a plane but rather spiraling upward in three dimensions.

Figure 1. Forward and Backward Silk Reeling

(Larger version)

Figure 1 Explanation:

1. The solid line is shun (forward) silk reeling and the dotted line is ni (backward) silk reeling

2. The numbered points on the chart are the places where the shun and ni silk reeling alternate

A. Left hand silk reeling B. Right hand silk reeling

II. The Function of Moving Energy in Silk Reeling Style Spirals

Figure 3. Spiraling Pulling Silk Movement

Figure 2. Simple Curve Movement

If as you practice Tai Chi the hands just extend out straight and retract straight without rotating the palms and the legs bow forward and sit backward without an accompanying left and right turning, this will produce the defect of directly resisting force with force. (see figure 2). In order to correct this defect, we must use spiraling energy. Because a spiraling curve leading a radius is transforming; if any pressure pushes against this spiraling pole it can easily lead the pressure into emptiness and so transform it. This is a scientific way to transform energy. From figure 3 you can see the function of it.

This spiral style of silk reeling is where “Tai Chi” gets its name. This type of spiraling exercise is uniquely Chinese and seldom found elsewhere in the world. From the viewpoint of physical training, this can help one make “all the joints link up” as you move and push 4 and from there advance to the realm of ‘matching inner and outer’ and ‘if one part moves all parts move’. This also has the function of creating a kind of massage for the internal organs. At the same time it stimulates the spirit manifested externally, strengthens the cerebral cortex, as well as strengthening the entire body structure and organs.

In addition silk reeling energy has important functioning for martial applications. The core of Tai Chi Chuan martial applications is the understanding energy referred to in ‘know yourself and know your opponent’ and ‘know opportunities and advantages’. Understanding energy can be divided into two categories: (1) understanding with regard to your own energy, which is to say understanding the energies of your own movements, to be obtained from form practice; (2) understanding with regard to the energy of others, which is to say understanding the energy of the other person, to be obtained from push hands. If you want to know others you must first know yourself; this is the process by which we gain understanding. If you want to make the self-knowledge gained from form practice advance to the realm of high levels of development, then you must learn the skill of practicing whole-body movement. The skill of whole-body movement is learned from making inner and outer match up and making all the joints connect up together, and these two are produced from spiral style silk reeling movements. Thus for martial applications, silk reeling energy is extremely important.

III. The Types of Silk Reeling Energy and their Essential Points

Shun Silk Reeling <---- Basic Silk Reeling ----> Ni Silk Reeling

|

Positional Silk Reeling

|

------------------------------------------------------------------------------

left-right up-down in-out big-small advance-retreat

Figure 4. Twelve types of silk reeling

According to qualities and capabilities, Tai Chi Chuan silk reeling energy can be divided into two basic types. The first is ‘forward’ (shun) silk reeling where the palms rotate from facing inward to facing outward. Within this group almost all consist of Peng (ward off) energy (see the solid lines in figure 1). The second type is ‘backward’ (ni) silk reeling where the palms rotate from facing outward to facing inward. Within this second group the bulk consists of L� (rollback) energies (see the dotted lines in figure 1). These two categories of silk reeling exist throughout the process of each Tai Chi Chuan movement, and are infused in it from beginning to end. As a result, within all moves is contained the alternation between the two energies: peng and l�; they are the basic contrasts within all movements and at the same time they transform into each other within a unified context. Because of differences in position and transformation, these two kinds of silk reeling can be further sub-divided by positioning into 5 types (see figure 4). Left-right and up-down positioned silk reeling together form a whole circle. Then if you add in in-out it makes the two-dimensional circle in a plane change to a three-dimensional circle, and that is precisely the quality that Tai Chi style spiral movement must have. Next, in order to have left and right returning to the beginning, connecting and following the opponent, all joints connected so the whole body works together as a unit, we add the two pairs big-small and advance-retreat, in order to satisfy special fitness and application needs. Therefore, in every movement of Tai Chi Chuan, above and beyond the basic ‘forward’ and ‘backward’ types of silk reeling, we have at least three pairs of positional silk reeling combined together. If you can only grasp this rule, as you circle in your movements you have a definite source of support for both learning and correction, making it all much easier. Whenever in your practice you feel that a move seems wrong or lacks energy, you can adjust the waist or legs to correct the spot where silk reeling is not appropriate, then you can correct the move. So getting a good grasp of the silk reeling can provide a tool for self correction. Let’s take a few examples to illustrate this.

(1) “Cloud hands” — This move, among the thirteen powers is the only one to include both doubled ‘forward’ changing into doubled ‘backward’ left and right large silk reeling. When you perform this move, the basic silk reeling of the two hands is ‘forward’ palms going from facing inward to outward, changing into ‘backward’ palms going from facing outward to inward. The positional silk reeling of cloud hands is left-right, up-down and a slight amount of in-out. Left-right and up-down make a circle in two dimension. If you then make the circling include a slight in-out, you can turn it into a three dimensional circle in space, enabling the qi to stick to the backbone.

(2) “White Crane Spreads Wings” — The basic silk reeling is one ‘forward’ one ‘backward’, which is a relatively common pattern in the form. The positional silk reeling is left-right, up-down, and in-out. Because it has one ‘forward’ one ‘backward’, as the left hand performs ‘backward’ silk reeling going in and down and the right hand performs ‘forward’ silk reeling going out and up, the combination of the two, according to the requirements for the connection between the two arms 5, results in right going up and left going down, a right ‘forward’ left ‘backward’ separate and ward off circle.

As the two examples above show, although the various movements of Tai Chi Chuan seem to have an awful lot of different shapes and different ways of transition, when analyzed from the point of view of their basic silk reeling, they are actually extremely simple. All the Tai Chi moves fall into one of three categories of silk reeling: “doubled ‘forward'”, “doubled ‘backward'” and “one ‘forward’ one ‘backward'”. If you use this method to analyse and work on the form you frequently practice, and put it into a chart format, this can become a good source of support for your practice. And with this kind of aid, you can become clear about the different kinds of energies, and achieve ‘inner and outer match up’ as well as ‘all the joints link together’ and thus on the basis of improving flexibility, attain to the proper requirements for correct postures.

IV. Getting a Grasp on Spiral Movement

Silk reeling, this third characteristic, is where Tai Chi gets its name, and functions as detailed above. That is why our predecessors, in order to help learners properly perform movements as though reeling silk, included a section in “Discussion of Tai Chi Chuan [Tai Chi Chuan Lun] devoted to this very subject as a practical summary of how to move energy. The first section discusses silk reeling energy. In order to get control of this third characteristic of Tai Chi, you just need to compare [your moves] to this portion as you practice and use it regularly as a standard when practicing the form, and then you can obtain correct postures and movements. Below we will summarize and explain this portion.

(1) Grasping the Third Characteristic Via Essential Spirit

A. “In each an every motion, the entire body must be light and nimble”. If you can raise your spirit, then you are able to avoid having dull and heavy thought processes; this is the way to achieve lightness. If your intent is able to change nimbly, then your intent will not get hung up on one point only; that is the way to achieve nimbleness. The first step to grasping silk reeling energy is for the entire body to be light and nimble during the process of movement. Only then can you set up favorable conditions to support silk reeling movements.

B. “In movement you must link all the joints together as a whole.” In moving like reeling silk, if you want to be light and nimble, it is particularly necessary to link together. This is an important environment for movement and must not be overlooked as you practice. For detailed analysis of this, please consult the section on the 5th characteristic of Tai Chi of the present chapter of this book.

C. “The spirit should be roused and the qi should be kept within.” 6 If the conscious mind cannot be concentrated on the movements and you think of other things then this will result in confused thought and clumsy spirit, and so the spirit will be difficult to rouse. At the same time you will also be unable to keep the qi within so as to follow the mind, and the result will be your qi and postures will be scattered, energy won’t be collected within, and the torso will move chaotically. Therefore, you must first and foremost anchor your thoughts to continuous and uninterrupted movement, and that way the spirit will naturally be roused. Next, you must make the breathing of the lungs coordinate with the movements. Because the spirit is roused, the qi is naturally kept within and doesn’t get scattered. When the qi isn’t scattered the spirit guides the head and inspires movement.

Summarizing the three requirements noted above, “In moving energy be light, nimble and linked together, with spirit roused and qi collected within” are mandatory essentials which must be grasped in order to grasp silk reeling energy.

(2) Grasping the Third Characteristic Via Energy Distinctions

A. “Don’t allow slippage.” When you utilize silk reeling energy, whether ‘going forward’ or ‘going backward’, endeavor to cause the 8 energies (ba men jing [translators note: earlier in the book identified as peng l�, ji, an, cai, lie, zhou, kan]) to move along the back of the spiraling curve. This is to say the spiraling contact surface must not be sometimes on the back of the curve, sometimes within the curve. This is the easiest defect to encounter in silk reeling. The moment you slip into the inside of the curve, not only do you weaken the peng energy, but you also lose the touch or contact quality of silk reeling. As a result, the moment you allow slippage, the energy cannot get to the contact surface of the spiral and you lose the silk reeling function of leading the opponent. (see figure 5).

Figure 5 Silk Reeling Slippage (text: “Slippage”)

Figure 6 Silk Reeling Indenting and Protrusion (left text: “Indenting” right text: “Protrusion”)

B. “Don’t allow indenting or protruding spots.” During the entire process, the route in which you employ silk reeling energy must be a smooth curve, forming smooth and even postures. At the same time, it is also required to be soft and rich in flexibility, and that is one way of getting rid of indenting or protruding spots. Even when you emit energy, you still must swing out like a supple whip. This way, because the body and hands are extended, the body and limbs are like an inflated tire, and in their contact with things have the ability to follow contours and stick against them. The moment you have indenting and protruding spots in moving energy, it creates corners or angles, producing defects of resisting force with force, and thus causes the movement of energy to lose its spiraling, turning function. (see figure 6).

C. “Don’t allow ending and resuming spots.” In the process of silk reeling, whether ‘forward’ or ‘backward’, always endeavor to reel to the end. When we say ‘to the end’ we mean not only arriving to the point where this move deploys its energy against its target but also to the place where it connects to the next move. Arriving at this point, via a folding transition 7, connect to the next silk reeling, taking the energy and connecting it to the next move. Since the energy does not end, there is no need for resumption. If you reel to halfway and the energy is cut off, and then resume it again – that is just wrong. Because once silk reeling has ending and resuming, this is a crack or opening. This crack or opening not only loses the function of leading the opponent, but also allows an opportunity and an advantage for the opponent. That is why we say this is not permitted in moving energy and silk reeling. (see figure 7). Beyond this, even when you emit energy, although there is a cutting off and resuming, you still must have the requirement: “the energy ends but the intent doesn’t, the intent ends but the spirit can connect.” This is what is known as [seemingly] cutting off but connecting back up again.

Figure 7 Silk Reeling Must Not Have Ending and Resuming

(upper and lower text: “This section must not have ending or resuming)

(Left and right text: ” Transitional folding area)

(left and right sides encircled word: “Slow”)

(Upper middle: Slow —>speeding up energy —> Fast)

(Lower middle: Fast <--- speeding up energy <--- Slow)

In summary the three entries above explain how in the process of silk reeling, which is also the process of moving energy, you must not have the defects of slippage, indenting or protruding, or ending and resuming. If even one of these three defects is present, you will be unable to deploy the proper functions of silk reeling energy. This is a problem which you must not ignore in your practice.

In order to facilitate grasping this topic, I will now summarize the requirements:

(1) Silk reeling energy is the source of the name ‘Tai Chi Chuan’. Without silk reeling energy we would not be able to make the energy circle round the body and limbs so all tend to rise upward, attaining to completion in one qi.

(2) We need to understand the requirement to ‘link everything together’. Not only does moving energy require going through all the joints, it also needs to be sent through the muscles and sinews above and below the joints. This is the function of spiraling silk reeling.

(3) Tai Chi Chuan has a pair of basic silk reeling categories as well as five pairs of positional types of silk reeling which make up one of the best tools for learning and teaching Tai Chi.

(4) ‘Move energy like reeling silk’ can only be accomplished under the conditions of lightness and nimbleness and linking everything together. At the same time, the spirit must be roused and qi kept within.

(5) In the use of silk reeling energy, you must avoid the three defects of slippage, indenting and protruding, and ending and resuming.

Footnotes

[author’s footnotes from original Chinese]

[1] In the unique small-frame Tai Chi of Yang Shaohou in his later years, one could only observe the emitting of energy and not the moving of it. This was because the circle of movement for energy was so small that you could not see it; one could only observe the emitting of it. That is the fullest development of circles so compact they were invisible.

[2] When we refer to rotating the palms from facing inward to facing outward or from facing outward to facing inward, we are using the index finger as the standard. For example in figure 1, when the hand goes from point 1 to point 2, the index finger rotates from inside to outside, so that is called shun (going forward). When the hand goes from point 2 to point 3, the index finger rotates from outside to inside so it is deemed ni (going backward).

[3] When we refer to the trajectory of the legs in silk reeling, we are using the the turning direction of the knee as the standard. So when the knee circles diagonally from close in to the crotch forward and turning outward and down, or starting from out away from the crotch circles diagonally backward turning inward and going upward, this is deemed shun (forward). When the knee circles diagonally from out away from the crotch forward turning in and up, or when the knee circles diagonally from in close to the crotch backward turning outward and down, this is deemed ni (backward).

[4] “All the joints link together” is the fifth characteristic of Tai Chi Chuan.

[5] The connection between the two arms means as you move, it is as though there is a string connecting the two arms, and when one arm moves, the other arm also moves under the condition that it is able to keep the string tight with peng energy. That is to say we need to always keep a peng energy between the two arms which makes them tend to pull apart.

[6] Spirit and qi can both be roused, and both can be kept within. That is why ‘Discussion of Tai Chi Chuan’ says: “If you want the spirit and qi to be roused, first raise the spirit, then the spirit does not get dispersed.”

[7] For the meaning of folding, see the 6th characteristic of Tai Chi Chuan. [maybe in a subsequent column we can look at this]

Thanks to Rocky Yang for providing a cleaned-up version of figure 1.

Translation Copyright © 2002 Gerald N. Karin. All rights reserved.

Yang Zhenduo’s Disciples

Master Yang Zhenduo is proud to announce and acknowledge the following people as his Disciples.

These individuals have studied and promoted tai chi for many years.

List edited 5/11/2015

Disciples Name List, 杨振铎传承弟子

| Yang, Jun | 杨军 |

| Yang, Bin | 杨斌 |

| Hu, Buyun | 胡步云 |

| Xie, Wende | 谢文德 |

| Yang, Liru | 杨礼儒 |

| Cheng, Xiangyun | 程相云 |

| Wang, Wen | 王 文 |

| Yan, Fengxiang | 闫凤祥 |

| Qiao, Rongjian | 乔荣建 |

| Geng, Ying | 耿 莺 |

| Yao, Junfang | 药俊芳 |

| Liang, Xiufang | 梁秀芳 |

| Yang, Yongfen | 杨永芬 |

| Wang, Dexing | 王德星 |

| Miao,Guangzhao | 苗光照 |

| Yang, Chunru | 杨春儒 |

| Zhang, Guilan | 张桂兰 |

| Jia, Cengping | 贾承平 |

| Tian, Xianwen | 田宪文 |

| Yang, Wensheng | 杨文升 |

| Wang, Baixuan | 王白玄 |

| Niu, Xinzhong | 牛新中 |

| Huo, Jiansheng | 郭建生 |

| Gong, Xinling | 弓心伶 |

| Bian, Xiuhong | 边秀宏 |

| Zhang, Weixian | 张未仙 |

| Liu, Taiduo | 刘太多 |

| Liu, Zhongke | 刘中克 |

| Bei, Dongrong | 白冬荣 |

| Li, Tiancai | 李天才 |

| Li, Rui???? | 李瑞蕤 |

| Li, Xianglian | 李湘莲 |

| He, Yong | 何 勇 |

| Lu, Yuqing | 芦玉琴 |

| Zhang, Baoe | 张宝娥 |

| Zhang, Jinkai | 张进凯 |

| He,Chenghong | 和成红 |

| Fan, Dezhi | 范德治 |

| He, Shengli | 贺胜利 |

| Guo, Xiaofang | 郭小芳 |

| Guo, Shulin | 郭树林 |

| Hao, Hongling | 郝红玲 |

| Hao, Xiaoyu | 郝晓玉 |

| Qin, Huiling | 秦慧玲 |

| Cui, Juan | 崔 娟 |

| Hou, Yuhua | 候玉华 |

| Qi, Lianxiang | 戚连香 |

| Jiao, Guiyun | 教桂云 |

| Chanf, Jianli | 常建立 |

| Hang, Jiandong | 黄建东 |

| Peng, Li | 彭 莉 |

| Shi, Jinhua | 史锦华 |

| Li, Qimei | 李七梅 |

| Ma, Jianjun | 马建军 |

| Wang, Zhiqiang | 王志强 |

| Li, Shengwu | 李生武 |

| Du, Shengyao | 杜生耀 |

| Yang, Jinxiu | 杨锦秀 |

| Li, Chunhou | 李存厚 |

| Qu, Qiaoyu | 曲巧鱼 |

| Yan, Weixi | 闫维喜 |

| Li, Xiuying | 李秀英 |

| Wang, Zhongwen | 王仲文 |

| Ren, Chunlin | 任春林 |

| Li, Ruizhen | 李瑞珍 |

| Ren, Zhaoji | 任兆基 |

| Zhang, Jiansheng | 张建胜 |

| Wei, Jianguo | 魏建国 |

| Luo, Haiping | 罗海萍 |

| Zheng, Juying | 郑菊英 |

| Luo, Haiying | 罗海英 |

| Jiang, Yafan | 姜亚范 |

| Gao, Feng | 高 峰 |

| Liang, Junhu | 梁军虎 |

| Song, Bin | 宋 斌 |

| Wang, Ying | 王 瑛 |

| Zhao, Qi | 赵 琦 |

| Ma, Jianguo | 马国华 |

| Xue, Jizhen | 薛继珍 |

| Qiao, Jianlin | 乔建林 |

| Gao, Junsheng | 高俊生 |

| Zhou, Yazhen | 周亚珍 |

| Gua, Xiaolong | 滑小龙 |

| Xin, Jiaan | 辛甲安 |

| Zai, Chaofeng | 翟朝峰 |

| Cai, Jiliang | 柴吉良 |

| Yang, Shufang | 杨树芳 |

| Wang, Suxia | 汪素霞 |

| Jia, Shumin | 贾淑敏 |

| Jian, Guixian | 简桂娴 |

| Zhang, Zhiyong | 张志勇 |

| Zhang, Suzhen | 张素珍 |

| Qi, Lin | 乞霖 |

| Li, Peng | 李 鹏 |

| Liu, Zhongliang | 刘忠良 |

| Ge, Jingang | 戈金刚 |

| Wang, Yuzhen | 王玉珍 |

| Qiao, Qingyun | 乔青云 |

| Du, Yanping | 杜燕萍 |

| Song, Chunxiang | 宋春香 |

| Sun, Gangchen | 孙刚臣 |

| Liu, Sen | 刘 森 |

| Zhao, Qing | 赵 清 |

| Zheng, Jinchong | 郑金崇 |

| Feng, Weihua | 冯维华 |

| Hou, Jihua | 侯继华 |

| Yuan, Yingying | 袁颖颖 |

| Lu, Dongmei | 卢冬梅 |

| Hu, Fuchuan | 胡富川 |

| Ma. Ping | 马 萍 |

| Xu, Yanguo | 许廷国 |

| Niu, Jianhua | 牛建华 |

| Song, Yuanzeng | 宋元增 |

| Wang, Jinxiu | 王进修 |

| Feng, Shoujun | 冯守俊 |

| Ma, Runliang | 马润良 |

| Yang, Zihua | 杨子华 |

| Gao, Aiping | 高爱萍 |

| Qin, Huizhen | 秦慧珍 |

| Liu, Xiying | 刘喜英 |

| Dong, Yuwen | 董郁文 |

| Yang, Peiji | 杨培基 |

| Liu, Duisen | 刘队森 |

| Li, Guoying | 李国英 |

| Ma, Fenping | 马粉萍 |

| Wang, Jinwang | 王晋芳 |

| Zhang, Lingdi | 张玲娣 |

| Yang, Chunxia | 杨春霞 |

| He, Congming | 贺聪明 |

| SunYueqing | 孙月庆 |

| Zheng, Junshu | 郑树军 |

| Zhao, Haiping | 赵海平 |

| Li, Hui | 李 慧 |

| Bai, Jinghu | 白景虎 |

| Song, Yanlin | 宋眼林 |

| Li, Jingjing | 李晶晶 |

| Wang, Cuilian | 王翠莲 |

| Dai, Shaopeng | 戴绍朋 |

| Zhao, Yixin | 赵一新 |

| Feng, Caixia | 冯彩霞 |

| Feng, Yanxia | 冯艳霞 |

| Chen, Jun | 陈俊 |

| Xu, Rong | 许蓉 |

| Gao, Wenjian | 高文鉴 |

| Du, Xinglong | 杜星龙 |

| Lim Chiew Aw | 林秋雅 |

| Theresa Teo Mei Mei | 张美美 |

| Han Hoong Wang | 王涵蓉 |

| Andy Lee Zalcman | 安蒂·李 |

| William P. Walsh | 比尔·沃尔斯 |

| Dave Barrett | 大卫·白瑞特 |

| Frank Grothstück | 费兰克 |

| Jean-Marc Geering | 马克哥润 |

| Andre Laray | 安德列·勒瑞 |

| Duan, Yinglian | 段英莲 |

| Li, Shoutang | 李寿堂 |

| Wang, Xiyou | 王熙有 |

| Wu, Zongfu | 吴宗福 |

Secrets

The Third Rep: 2001-02-12

by Jerry Karin

Well, time to whip out the old notepad and scribble a new third rep column. Having had my posterior flamed from here to Yongnian over a previous column entitled Some Other Stuff and subsequent postings in the same vein on the discussion board, you would think I would know better by now, but apparently once begun the habit of letting ‘I dare not’ wait upon ‘I shall’ grows ever easier.

Back around 1972 when I was a student at Berkeley, my instructor in a class on Buddhism invited a very high-ranking monk in the hierarchy of a large Buddhist sect in South Korea to speak to the class one day. The monk, a kind, gentle and humble person, used the hour to tell us the story of a famous monk in Korean Buddhist history. I heard this tale nearly thirty years ago so I am undoubtedly going to mangle some of the details of the story, but I think I have got the gist of it.

The events in the story took place early in Korean Buddhist history when teachings about Buddhism were difficult to get in Korea and it was the dream of many a searcher to voyage abroad to China, where they hoped to find more advanced knowledge about Buddhism. A young monk, embarking on this course, traveled from his home to a seaport to begin his long journey to China. The evening before he was to board a ship to China, having had a meal at a local temple, he wandered out into the warm night and came to a beach, where he decided to spend the night. In the middle of the night he awoke with a fierce thirst which simply could not be denied, and started looking around trying to find a puddle of rainwater from which to drink. There was a dim moon out and he suddenly spied its reflection in a large container of water, sitting on a log. Delighted, he picked it up and tasted it. He found it the most delicious thing he had ever tasted and gulped down long draughts of the water until his powerful thirst was satisfied, whereupon the sleepy monk lay back down and was soon snoring.

As the sun rose on the morning his great journey was to begin he awoke and looked around for the container of water that he had found the night before. To his dismay he discovered that he had been sleeping in one of those ‘air burial’ grounds to which Buddhists are partial, where decomposing bodies of the dead are left in the open for birds and animals to eat. The log was a corpse and the container of water which had tasted so delightful the night before turned out to be a human skull, with some vestiges of flesh still clinging to it. His horror rose in him physically and he vomited again and again. Suddenly he experienced a moment of awakening about the nature of existence, illusion and reality. The monk never boarded the ship for China. The answers which it had once seemed necessary to search out far away in another land turned out to lie within himself. This monk went on to become one of the great founders of Buddhist study in Korea.

Now from the sublime to what I hope will not be too ridiculous. I first met the Yangs in 1993, at a seminar they gave at Hood College in Maryland. I remember well my first glimpse of Yang Zhenduo. Chris Pei was escorting Yang Zhenduo and Yang Jun to the opening dinner reception. A bunch of students gathered around to greet them and Yang Zhenduo made a little impromptu speech, saying we had a great deal to cover in one week, but that he knew we would succeed because we would work hard….. He spoke in a beautiful, pristine northern mandarin, very reminiscent of my first Chinese language teacher, who had grown up in Peking. His manner, diction, everything about him made him seem the most traditional Chinese person I had ever met, though I had lived in Taiwan for many years. I was powerfully intrigued, and the seminar itself lived up to the expectation I formed at that moment. Here was a teacher steeped in the real tradition.

Over the years I continued to attend seminars, all the while trying to come up with a scheme which would allow me to go to China for an extended period of time and really learn the secrets of Yang style taiji which the Yangs clearly had in such abundance. The demands of work and family never did allow me to follow through on the idea. Then one day a couple of years ago I learned the most astonishing news: through no effort of my own, and unbeknownst to me, Yang Jun had been preparing for some time to move to my very doorstep here in Seattle! I couldn’t believe my luck. When he arrived here I went to classes whenever I could. I learned quite a bit. Still, the demands of work and family did not go away. Yang Jun had moved here but I was still the same person, working full time, taking care of a child, spending time with my wife, doing all the mundane things I have always done. The truth was I rarely had time to attend classes. Practice time was also difficult to find. Gradually my dream of getting the real secrets from the Yangs faded.

About a year ago I had an extended period of unemployment between jobs. Unfortunately, for most of that time, Yang Jun was away giving seminars around the world. I subbed for him in some of his classes in Seattle. Yang Jun had asked me to make a new translation of Yang Chengfu’s essay, “A Talk on Practice” for the Association newsletter, which I did (you can see it in the info section of this web site). Translating focuses your attention on the content in a way that casual reading seldom does. In the essay Yang Chengfu mentions that you really should practice the barehand form seven or eight times a day. I remembered how good it felt working out many hours a day during the seminars. Since I had some time while I was job-hunting, I decided to try seven reps a day. The idea is to consciously work on the ten essentials while doing all those reps. This for me was the beginning of learning the real secrets of taijiquan. I discovered that it had never been necessary to go to China, wonderful as that would have been. Yes, you do need to get the basics from a good teacher. The real secrets, however, are revealed by practice.

Palm Methods (Zhang Fa)

From Yang Zhenduo’s

1997 Zhong Guo Yang Shi Taiji, pp. 33-36

Translation by Louis Swaim

The palm methods are a sub-category of the hand methods. The palm methods can be broadly divided into two classes, comprising approximately nine types.

The first class, “seated wrist upright palm” (zuo wan li zhang xing) contains five types of palm methods:

- standing palm (li zhang)

- square palm (zheng zhang)

- downward palm (fu zhang)

- outward turned palm (fan zhang)

- level palm (ping zhang)

The second class, “straight extended” (zhi shen xing), contains four types of palm methods:

- upward palm (yang zhang)

- inclined palm (ce zhang)

- downward hanging palm (chui zhang)

- straight palm (zhi zhang)

One: The special characteristics of “seated wrist upright palm” are that when the palm extends forth it must always have the wrist seated and the palm upright. As for its technique, above all, the wrist of the hand must sit solidly. Then, allow the palm of the hand to stand up; that is, lift it upwards, and gradually let the fingers point up and the heart of the palm face forward. When the standing up of the palm reaches a certain degree, it will then produce a kind of internal sensation (nei zai de ziwo ganjue). This type of sensation is called “energy sensation” (jin gan). If the practitioner’s physical training has a firm foundation, this type of “energy sensation” can immediately thread throughout the entire body. Beginning students, however, may manifest a local sensation of stiffness (the hands and arms ache or become numb).

The above two categories of sensation are entirely different. In light of this, beginning students should above all avoid raising the palm insufficiently, with the production of weak, hollow, and nebulous sensations. However, a stiffness or dullness produced by an excessive lifting upward is also not the goal of our pursuit. If you can only feel the sensation of energy, then if it is not right, you can correct it. But if you can’t sense it then it will be empty, and cannot be self-adjusted. This palm method controls, in a clearly established order, the containing of energy (jin), the expression of vital spirit (jingshen de biaoda), and the achievement of hardness [within] softness, with the result that it will penetrate [or ‘thread’] from joint to joint (jie jie guan chuan), and the entire body will be coordinated. In order to train well in Yang Style Taijiquan, you must seek this “energy sensation” in the upright palm.

The following are a few methods of the “seated wrist upright palm”.

- Standing palm (li zhang) When the fingers point up, or incline upward, and the palm does not face squarely forward, but in another direction, this is called standing palm. An example is the upper palm in Brush Knee Twist Step, and Step Back Repulse Monkey; the lower palm of Jade Maiden Threads the Shuttles, etc.

- Square palm (zheng zhang) When the fingers point up, and the palm faces forward squarely, this is called square palm. Examples are the Push (An) in Grasp Swallow’s Tail, and in Like Sealing As if Closing, etc.

- Downward palm (fu zhang) When the heart of the palm faces down, or obliquely downward, no matter what direction the fingers point to, this is called downward palm. Examples are the lower palm in Brush Knee Twist Step, Wild Horse Parts its Mane, White Crane Displays Wings; the left palm in Punch Downward, and Punch to Groin, etc.

- Outward turned palm (fan zhang) When the fingertips point to the side, or obliquely to the side, and the palm faces outward, this is called outward turned palm. Examples are the upper palm in Jade Maiden Threads the Shuttles, White Crane Displays Wings; and the palm as it turns from Ward Off (Peng) to Pluck (Cai) in Cloud Hands.

- Level palm (ping zhang) Regardless of the direction the fingers point, the palm faces down or circles levelly to the left or right. Examples are the transitions to Single Whip, or Observe Fist Under Elbow.

The above palm methods are all based on the seated wrist and upright palm form. If, when performing these postures, one does not seat the wrists and make the palm upright, there will appear in the body a looseness and softness, a nebulous emptiness. Experiment with this, then you will be able to make an appraisal.

Two: The special characteristics of “straight extended” and its techniques are: You only need to have the palm extended straight (not rigidly stiff) — let it be level, let it be expanded and drawn out, then you will have it. This does not require that the wrist be seated and the palm upright, but it also has the self-sensation of internal energy (nei jin de ziwo ganjue), and a penetration throughout the entire body. Although there are differences with the seated wrist upright palm in the expression in shape and form, as well as in methodology, the action and results produced are the same. The two are interdependent and work in mutual coordination. One should regard them equally.

The following are a few methods of the “straight extended” palm:

- Upward palm (yang zhang) In cases where the heart of the palm is up, or obliquely upward, and the fingers point forward or incline forward, this is upward palm. Examples are the lower palm in Step Back Dispatch Monkey, and High Pat on Horse; or the upper palm in Oblique Flying, or Piercing Palm [of High Pat on Horse with Piercing Palm].

- Inclined palm (ce zhang) When the palm is toward the inside or inclined to the inside, regardless of what direction the fingers point, this is called inclined palm. Examples are Left and Right Ward Off in Grasp Swallow’s Tail, and Ward Off in Cloud Hands, etc.

- Downward hanging palm (chui zhang) When the palm is facing in or inclined toward the inside, and the fingertips point down or incline downward, this is called downward hanging palm. Examples are the two arms hanging down in the Preparation Posture, or when the arms orbit down in rounded arcs, etc.

- Straight palm (zhi zhang) When the palms are down or inclined downward, regardless of the direction the fingers point, this is called straight palm. Examples are the turning transition from Push (an) to Single Whip, the two arms rising upwards in the Beginning Posture, etc.

When the Taijiquan postures are in the process of circling, there emerges a reciprocal alternating and advancing of the various palm methods. For example, in transitioning from White Crane Displays Wings to Brush Knee Twist Step, the right arm circles down from above to in front of the thigh (kua). The palm is up, the fingers toward the front, forming an upward palm. Continuing down in a circular arc, the palm turns toward the outside, the fingers pointing down, forming a downward hanging palm. Now again the arm bends upward, turning the fingers to point up, the palm facing obliquely outward, forming a standing palm.

Regarding whether in the above discussion there is a relationship between the palm methods (zhang fa) and the proper hand shape (shou xing), they both have an indivisible relationship. As to hand shape, it has already been explained in the “Ten Essential of the Art of Taijiquan”: “The palm should slightly extend (zhang yi wei shen), the fingers should slightly bend (zhi yi wei qu)”.* However, in actual practice, there is still another requirement: “The spaces between the fingers should be slightly open “. This is also important, and requires that the fingers not be gathered together, and also that they not stretch wide apart. In this way the outer shape and appearance of the palm of the hand will increasingly tend toward perfection, there will be hardness contained within, and it will still have a pliable outward appearance, natural — refined and elegant — one could say that form and spirit are complete and prepared (xing shen ju bei). It is hoped that students will memorize (mo shi), comprehend (ti wu), and ponder (chuai mo).

One’s ability to accomplish each of the palm methods rests entirely on the foundation of “fang song” (relaxing, loosening). If you are able to properly understand the significance of “fang song”, and your practice is correct, there is sure to be a good result. Because of this, one must have proper guidance in one’s training — only then will you be able to utilize each type of palm method correctly, and gain the result of one palm representing the entire body.

Translator’s Note:

[*] I looked for this sentence in Yang Chengfu’s “Ten Essentials of the Art of Taijiquan” (Taijiquan Shu Shi Yao), but it does not appear there. It does appear in Yang’s “A Discussion of Taijiquan Practice” (Taijiquan zhi Lianxi Tan).

Relaxation (Fang Song)

Excerpted from Yang Zhenduo’s

Zhong Guo Yang Shi Taiji, 1997, ‘Thoughts on Practice’ p163-164

Translated by Jerry Karin

2. Earlier in this book I have already talked quite a bit on the subject of ‘fang song’ or relaxation. Let’s connect related concepts by separately mentioning the terms ‘soft’ (rou) , ‘limp’ (ruan), ‘strength’ (li) and ‘energy’ (jing) so that these can be distinguished, which is helpful in practicing taijiquan.

In martial arts, we often hear the analogy made between ‘steel’ and ‘energy’ (jing). Likewise, ‘coarse strength’ (juo li) can be likened to ‘iron’, because ‘steel’ comes from ‘iron’ and the source of ‘energy’ is also naturally from ‘coarse strength’. Coarse strength is natural strength and is an inherent product of the human body. Coincidentally, the current graph used in Chinese for ‘energy’ (jing) includes ‘strength’ (li) with ‘work’ (gong) added to it. I am not sure if this was really the intent of those who designed this graph, but looking at this graph can surely help serve to explain the relationship of the two.

‘Adding work’ or refining, refers to the way in which, during the process of production, we use the method of high temperature forging; correspondingly for coarse strength we use the method of relaxation (fang song) to remove the stiffness of coarse strength. Both are means to an end.

The process of refinement causes the two to manifest something which seems contradictory to its original nature. For example the water used for tempering steel and drinking water seem similar, yet there is a difference in the nature of the two. The water used to temper steel – like the removal of the stiffness in coarse strength – brings about a flexible resilience. Drinking water, on the other hand, is ‘limp’; it does not have this nature of bringing about flexible resilience. Therefore when we refer to ‘coarse strength’ – which has had its stiffness removed – as soft but not limp, it is because ‘soft’ has this flexible resilience, which is to say it includes within it the ingredient for ‘energy’ . This is just what the late Yang Chengfu meant by “Tai Chi Chuan is the art of letting hardness dwell within softness and hiding a needle within cotton”. If the factor of ‘energy’ is not present, this is ‘limp’. ‘Limp’ is not the same thing as ‘soft’.