By Dave Barrett

Association Journal Editor

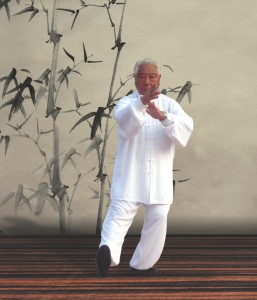

Master Ma Hailong was born in 1935 into one of China’s most distinguished martial arts families. His great-grandfather, Wu Quanyou (1834-1902), was an officer of the Imperial Guards Brigade in the Forbidden City. At this time, Yang Luchan (1799-1872) was a martial arts instructor in the Yellow Banner camp and for many years Wu Quanyou studied with Yang Luchan and his eldest son, Yang Banhou. Due to the protocols of the day, he could not be accepted as a direct disciple of Yang Luchan as Master Yang had aristocratic students and a military officer could not be in the same class as these more august individuals. However, Wu Quanyou’s training was with Yang Luchan directly and over the decades of his study he became renowned for his skills in interpreting and neutralizing an opponent’s energy.

Master Ma Hailong was born in 1935 into one of China’s most distinguished martial arts families. His great-grandfather, Wu Quanyou (1834-1902), was an officer of the Imperial Guards Brigade in the Forbidden City. At this time, Yang Luchan (1799-1872) was a martial arts instructor in the Yellow Banner camp and for many years Wu Quanyou studied with Yang Luchan and his eldest son, Yang Banhou. Due to the protocols of the day, he could not be accepted as a direct disciple of Yang Luchan as Master Yang had aristocratic students and a military officer could not be in the same class as these more august individuals. However, Wu Quanyou’s training was with Yang Luchan directly and over the decades of his study he became renowned for his skills in interpreting and neutralizing an opponent’s energy.

Master Ma’s grandfather, Wu Jianquan (1870-1942), was a cavalry officer who subsequently taught T aijiquan and developed from his father’s art what is now the Wu Style. Utilizing the “small frame” his father had learned from Yang Luchan, he made important modifications utilizing narrower circles and the distinctive foot work and body positions now seen in Wu Style Taijiquan. In 1914 along with his colleagues Yang Shaohou, Yang Chengfu and Sun Lutang, he began teaching publicly at the Beijing Physical Culture Research Institute. As he taught the general public he continued to make modifications to his style, refining the more overt martial techniques in much the same way that Yang Style has, making the motions slower and smoother for a wider appeal. In 1928, Wu Jianquan moved to Shanghai and formed the Jianquan Taijiquan Association in 1935.

Master Ma’s father, Ma Yueliang (1901-1998), began studying with Wu Jianquan at the age of 18. In 1930 he married Master Wu’s daughter, Wu Yinghua (19061996), and served as deputy director of the Shanghai Association.

From the age of 6, Master Ma began learning Taijiquan in this especially rich environment. Both his parents were accomplished teachers and his uncles had studied intensively with his grandfather. He remains dedicated to this day to sharing his family’s traditions.

The war years with Japan and the subsequent Revolution were not kind to Master Ma’s family. One of his uncles languished in prison for 30 years. The Shanghai Jianquan Taijiquan Association went underground during the Japanese occupation as the Japanese banned any martial arts activities. Master Ma’s eldest uncle, Wu Kungi, moved to Hong Kong and established a new headquarters for the Association which has flourished internationally and is now headed by his nephew, Eddie Wu. Master Ma’s family had to continue to practice underground during the Cultural Revolution and after 30 years in the shadows, the Shanghai Jianquan Taijiquan Association re-opened in 1978. During a brief visit with Master Ma last summer in Taiyuan I had a chance to ask him about this:

DB: For how many years did your family have to practice underground?

MH: From 1948, the Shanghai Wu Style Association was closed until 1978.

DB: During those 30 years were people still practicing Wu style?

MH: Because Wu style Taijiquan had a very good foundation in the Shanghai area even though our Association was closed, many people still practiced.

DB: So when the Association re-opened in 1978, this must have been a very happy day for your father and mother. From that point the rest of the world began to learn about your father Ma Yueliang and he began to travel.

MH: My father went to Europe with my mother and began to teach internationally.

DB: So now the Shanghai Association is going strong? MH: From my point of view, I feel we could be stronger. One of the difficulties in Shanghai is that not very many young people are joining our practice. Most of our members are middle-aged and older. If we don’t have young people studying this is a problem. I am putting more energy into developing younger people and drawing them into our practice.

DB: Are young people in China today so busy: focused on career, on gaining wealth, is this why they are not interested?

MH: This is one reason, secondly many new sports have recently become popular in China especially basketball, tennis and soccer. Another reason is that our traditional practice takes a long, long time to develop. It’s not like one or two days of practice or a few months, or even one or two years of practice to get a good result. This makes it difficult to attract young people.

DB: My feeling is that Tai Chi practice gives one a certain amount of peace, contentment, and happiness that other sports do not. This is a special quality. All over the world there is the same problem with young people, so many choices and distractions. Once they can taste this peace through practice, this may draw them in to study Tai Chi.

MH: What you say is excellent and I agree with your point. We are starting to emphasize this in our outreach activities to young people.

DB: I’ve read that your father, Ma Yueliang’s special skill was central equilibrium and his ability to neutralize incoming force. Can you describe how Wu style developed this skill?

MH: The ability to neutralize energy developed because early on the founders of Tai Chi realized that there was something missing from other styles of Chinese martial arts. They also combined Chinese philosophy with their techniques. For example, neutralizing incoming force does not just depend on using your own strength; it utilizes the opponent’s energy to strike back.

DB: So how do we do this? By rotating the central axis of the body?

MH: Basically you need to find the point of balance in your opponent and make it easier for them to lose their center.

DB: Many say that it was very difficult to find your father’s center.

MH: His skill at Push Hands was extraordinary. Most opponents could not find his center. This technique comes from long practice. My father and uncles and members of their generation practiced all the time. My brother, Ma Jiangbao, lives in the Netherlands and his technique is pretty good, almost like my father’s. He has some students who are quite skilled as well. So from daily, daily practice they begin to acquire this skill.

DB: This ability goes back to Wu Quanyou and his development of yielding skills and can we consider this a special quality of Wu style Tai Chi Chuan?

MH: For Wu style, neutralizing ability is one standard aspect of our practice. Another key to our practice is that it must be quiet, calm and tranquil. If you cannot enter into tranquility during practice, you cannot develop your skills very well. In our Wu Style, we have 5 concepts that guide our practice: 1st is calm, 2nd is slow, 3rd is lightness, 4th is serious practice, and the 5th is non-stop study. You must practice every day!!

DB: Many international students practice maybe once or twice a week, perhaps only during class time, and take the rest of the week off. So what can you say to these friends to encourage them to practice every day?

MH: In practicing Tai Chi, I feel it is best to practice every day for a sufficient period of time, for example, every day for an hour of practice. It doesn’t matter morning or evening, that’s OK, but you should do it every day. So we have a concept in Tai Chi that describes conserving or storing vital energy. It’s like you are saving money in a bank! By practicing every day you are gathering and storing this energy constantly. If you practice one day and stop for two days you won’t improve. My father and uncles practiced 5 hours a day. Every day they would arise before dawn at 5 am to begin practice, until 8 am and then practice in the evening as well. It is a special aspect of Tai Chi study that you cannot learn in one day; it is a very gradual process.

DB: What draws the student onwards, to practice more intensively? My personal feeling is that my practice brings me relaxation, peace and happiness. Is this a correct focus for our development of serious practice?

MH: In the past we said, “Exercise your body to improve your spirit”. This is a Confucian principle. This is an important element of our philosophy: body, mind and spirit, heart, your thought process, all can be improved by daily practice. More importantly, you are not just practicing to improve yourself; your practice affects others as well. You develop a sense of equanimity. Through your exercise this has a positive effect on society. One Confucian saying was, “good people also love other people”. Another aspect of this philosophy is that you should focus on taking care of your family. Thirdly, use your energy to help society.

DB: My personal experience is that Tai Chi practice has a very positive affect on the personal, familial and social spheres of the student.

MH: Practicing Tai Chi Chuan has this ultimate result: not only is it good for your personal health, it effects others as well. So that when you practice, not only focus on your personal development, but also take care for other people. This is very important.

DB: Let me thank you for these special insights. Many of our international group here in China talked to me about you by saying, “Oh, Master Ma Hailong, he seems so happy. He seems like a very nice man.” After having talked with you, I can understand more about how you personally have this special quality. It comes from your attention to everyday practice. Thank you so very much.

MH: After I return to Shanghai I’ll send you some more research materials to continue your study. ☯

Reprinted from Journal 25, Tenth Anniversary Issue, Summer 2009